Per – and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large group of synthetic chemicals characterized by a chain of carbon atoms bound to fluorine atoms through a process called fluorination.1 PFAS are a class of thousands of chemicals known or suspected to be endocrine-disrupting chemicals. According to the Endocrine Society and the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), “Endocrine disrupting chemicals are individual substances or mixtures that can interfere with our hormones’ natural functioning, leading to disease or even death”.2 PFAS are called “forever chemicals” because they don’t biodegrade. Instead, PFAS accumulate in the environment and our bodies over time.3 They are used to make consumer products nonstick, oil- and water-repellent, and resistant to temperature change. PFAS are used in many consumer products such as food packaging, nonstick cookware, water-repellent clothing, personal care products, and cosmetics (e.g., shampoo, dental floss, nail polish, eye makeup) as well as paints, sealants, stain-resistant carpets, upholstery, and other fabrics.3-5

Exposure to PFAS is associated with decreased infant and fetal growth as well as decreased antibody response to vaccines in both adults and children, according to a report by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM).6 Some of the most studied PFAS, such as PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) and PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid), have been linked to serious health problems such as cancer, obesity, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, decreased fertility, pregnancy-induced hypertension, birth defects, liver damage, altered immune response, and hormone disruption.2,7,8,9 Studies are now finding similar health impacts from some of the newer PFAS. The NASEM has called for people at higher risk, such as pregnant women, young children, and the elderly, to be tested for a subset of PFAS chemicals.6

The American Heart Association (AHA) published a scientific statement on environmental exposures and pediatric cardiology, which stated: “ample evidence identified to date connecting EDCs [endocrine-disrupting chemicals] and childhood cardiovascular risk factors is especially remarkable given the many challenges of the field”.9 The AHA concluded there is “[a] need for clinicians, research scientists, and policymakers to focus more on the linkages of environmental exposures with cardiovascular conditions in children and adolescents.” Finally, in this scientific statement, it is reflected that improvements in reducing environmental exposures have not occurred in an equitable manner9 as exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals disproportionally affect racial minorities, low-income communities, and other disadvantaged groups.10 As such, environmental health is a core feature of social and environmental justice.9-10

Individuals are exposed to PFAS in numerous ways including:

- Drinking water from PFAS-contaminated municipal sources or private wells

- Eating fish caught from water contaminated by PFAS (PFOS, in particular)

- Eating food products such as meat, dairy, and vegetables produced near locations where PFAS were used or made

- Eating food packaged in material that contains PFAS

- Accidentally swallowing or breathing contaminated soil or dust

- Accidentally swallowing residue or dust from consumer products such as stain-resistant carpeting and water-repellent clothing, and

- Ingestion of residue and dust from PFAS-containing products4

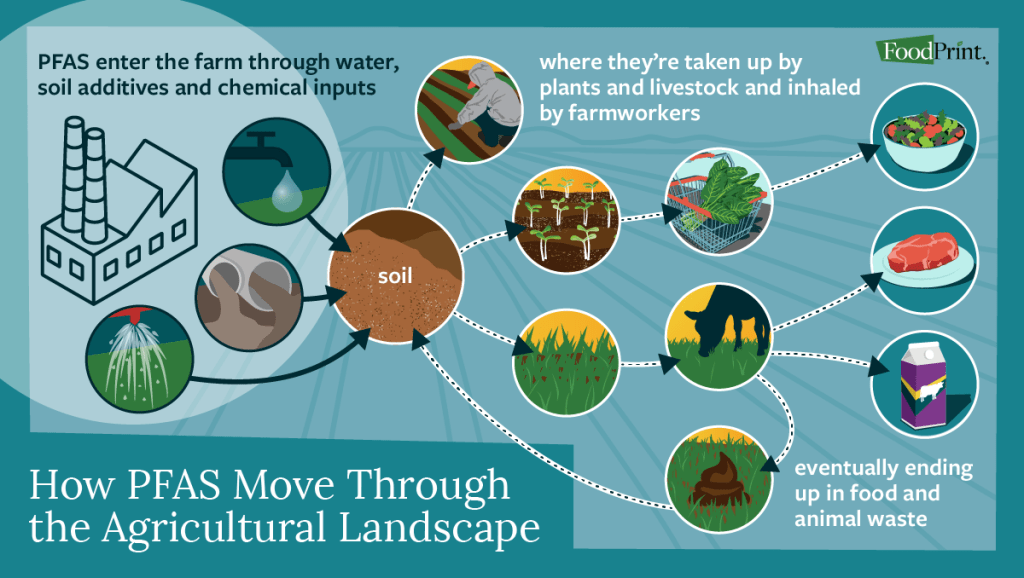

PFAS can enter a farm through water, soil additives, sewage sludge, and synthetic chemicals, such as pesticides. They are then taken up by plants and livestock and inhaled by farmworkers and farmers. Eventually, they end up in food and animal waste.1 See Figure 1 for an overview of how PFAS move through the agricultural landscape.

Figure 1. How PFAS Move Through the Agricultural Landscape1

A recent study found that greater consumption of processed meats, tea, and food prepared outside of the home was associated with increased levels of PFAS in the body over time.11-13 Processed meats could be contaminated with PFAS during the manufacturing process.13-14 Some foods analyzed were only associated with higher PFAS levels when they were prepared outside the home. People who ate foods such as French fries or pizza prepared at restaurants typically showed increased levels of PFAS (forever chemicals) in their blood. The researchers suggested that food packaging was the problem.13 The authors of this study observed the strongest associations between PFAS concentrations (more specifically, PFOA, one of the most well-studied types of PFAS) and heightened pork and tea intake.11-13 These researchers noted that the association between high levels of PFAS and tea intake could be linked to tea bags treated with PFAS chemicals (forever chemicals) – although more research is needed.13,15

In 2023, a study analyzing 108 tea bag samples collected from the Indian market found that PFOS, PFHxS, and PFuNA (PFAS chemicals) “were abundantly present in the tea bag powder and tea bag material.” Ninety percent of the tea bags contained detectable concentrations of PFAS.15 The research team at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California is currently “conducting research on the extent of PFAS contamination in popular tea brands as well as a follow-up study on diet and PFAS levels in a multi-ethnic group of participants.”11

Switzerland’s Food Packaging Forum Foundation identified 68 PFAS ‘forever chemicals,’ in food packaging including plastic, paper, and coated metal packaging. Of the 68 identified PFAS compounds, 61 had been previously banned for use in food packaging. These researchers identified hazard data that was available for 57% of the PFAS compounds detected in food packaging.16-17 Based on their assessment, they concluded that “the data and knowledge gaps presented here support international proposals to restrict PFASs as a group, including their use on food contact materials, to protect human and environmental health”.16

On April 10, 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced new standards for the regulation of PFAS chemicals in drinking water. The limits, known as maximum contaminant levels, or MCL, are the highest level of contaminant allowed in drinking water. These limits consider health concerns and water treatment costs and feasibility. The new MCL require water treatment plants to lower the amount of these chemicals to safer levels than currently exist in water systems.21 The new rules require municipal water systems to track and monitor the levels of PFAS, provide $1 billion in funding available to local governments to test and treat public water systems, and help owners of private wells address PFAS contamination. Water officials have 5 years to comply with the new limits.3 Public health advocates say the rules are an important first step, but are limited in their impact on the broader PFAS crisis. The new rules address only six compounds while about 15,000 PFAS exist, and the vast majority remain unregulated or unstudied. Drinking water represents only about 20% of human exposure, the EPA estimates, and diet is most likely a greater source of exposure.22

HOW TO LIMIT EXPOSURE TO PFAS CHEMICALS

Filter your tap water. Reverse osmosis filters are the most effective. To remove a specific contaminant such as PFAS from drinking water, consumers should choose a water filtration device that is independently certified to remove a contaminant by a recognized lab.23 Reputable third-party testing organizations include NSF, formerly known as, the National Sanitation Foundation (NSF), Water Quality Association (WQA), International Association of Plumbing & Mechanical Officials (IAPMO), UL Solutions, CSA Group, and Intertek (ETL). For a filter that can remove PFAS, look for one with the code NSF/ANSI 53, or NSF/ANSI 58 for reverse osmosis systems, followed by the manufacturer’s claim that the product can remove PFAS.23 NSF has a list of recommended filters available at: nsf.org. The Environmental Working Group (EWG) has also published a guide with recommendations on the most effective water filters for reducing PFAS, which is available here: EWG’s guide to PFAS water filters.

There are no standards for PFAS in bottled water.4 Save money, skip the plastic, and drink filtered tap water instead of bottled water.

Food, food packaging, and tea bags. PFAS compounds can bioaccumulate in crops, fish, and livestock.1 PFAS are used to make food packaging such as paper plates, bowls, bags, some plastic packaging, sandwich wrappers, and other types of packaging to make them water- and oil-resistant. A recent study found higher PFAS levels in certain foods prepared in restaurants such as pizza and French fries.13 To reduce your exposure to PFAS:

- Skip microwave popcorn – pop your own popcorn instead – either with a hot air popper or on the stove

- Limit consumption of highly processed meats (e.g. hotdogs)

- Limit food packaged in paper board and paper-based takeout packaging such as pizza

- Limit fast foods prepared at restaurants such as pizza and French fries

- Prepare home-cooked meals more often5,13

- Use uncoated paper products and products made from materials other than paper, such as bamboo24

- To store food – at home and away from home, use glass instead of plastic containers.24-26 Compostable containers, although plastic-free, may not be PFAS-free.24-25 Look for compostable packaging that is BPI-certified.27-28

- Tea bags treated with PFAS (forever chemicals) may be associated with increased levels of PFAS in the body over time, although more research is needed.13,29 If this issue concerns you, purchase loose-leaf tea or prepare your own tea at home.

For more information on how to limit PFAS exposure, visit Toxic-Free Future at: toxicfreefuture.org.

Cookware. If a pot or pan becomes damaged, consider a replacement. Through repeated use, non-stick cookware begins to scratch and chip. Use kitchen cookware free from PFAS including stainless steel, cast iron, ceramic, and glass. Carefully choose cookware. Beware of nonstick cookware that claims it’s free of PFOA, a PFAS that has been phased out. The cookware may have just-as-toxic replacement chemicals.5,30

Continue to breastfeed your baby. Research suggests that the benefits of breastfeeding far outweigh the risks of potential PFAS exposure. Due to the many benefits of breastfeeding, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend that most nursing individuals continue to breastfeed.4 The focus should be on reducing maternal exposure.30 Infants can be exposed to PFAS from drinking formula that is mixed with PFAS-contaminated water.4,30 To address this issue, use filtered tap water when preparing infant formula.

Check fish, game, and agricultural advisories. PFAS have been widely detected in locally caught freshwater fish in the United States. Check your local or state and environmental quality departments for fish or hunting advisories.4,30 “National testing done by the U.S. EPA shows that nearly all fish in U.S. rivers and streams and the Great Lakes, have detectable PFAS, primarily PFOS.” As such, “This is an example of social and environmental injustice facing communities that depend on catching fish for cultural practices or economic necessities”. 31

If you consume seafood, do so as part of a balanced diet. U.S. FDA testing shows that seafood purchased at grocery stores have significantly lower levels of PFAS than self-caught freshwater fish.31 “Though PFAS are more dilute in ocean water than they are in fresh water, marine life can also be contaminated”.1 In a recent study, scientists analyzed levels of 26 different forms of PFAS in salt and freshwater fish, including cod, haddock, lobster, salmon, scallops, shrimp, and tuna. They found that shrimp and lobster had the highest concentrations of PFAS, with averages ranging up to 1.74 and 3.30 nanograms per gram of flesh, respectively, for certain PFAS compounds. Concentrations fell to less than one gram of PFAS per gram for other types of seafood.32 Based on these findings, the authors concluded, “high seafood consumers may be exposed to PFAS concentrations that potentially pose a health risk.” They further stated that their findings support the “future development of environmental and health-based policies to protect people from exposure to PFAS found in commonly consumed seafood”.32

Clothing, textiles, and dust. Purchase clothing items from companies that have made commitments to not use PFAS in their products. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), “The best way to find out whether your item of clothing is PFAS-free is to check the brand’s website to see if it has announced that it has eliminated PFAS from its clothing or labeled clothing lines as PFAS-free”.28 If no information is available, contact customer service to ask directly. Review the brands covered on NRDC’s PFAS apparel scorecard. Also, you can check out PFAS Central, a project of the Green Science Policy Institute, which offers a helpful list of products and brands that state they offer PFAS-free outdoor gear, apparel, and other products.28

Avoid waterproofing stain-proofing treatments, unless advertised as free of PFAS. Vacuum frequently using a vacuum fitted with a HEPA filter to eliminate household dust that may contain PFAS.4-5,33 Opening windows can help filter out dust as well.33 While these are important steps consumers can take to limit exposure to PFAS, scientists believe they aren’t enough to control PFAS contamination. Their pervasiveness in the environment makes it impossible to avoid exposure, according to Dr. Carmen Messerlian, a Professor of Reproductive Environmental Epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who studies PFAS. Dr. Messerlian reflects that: “Even someone like me, a scientist and a mother who cares about human health, can’t avoid PFAS chemicals. I can chip away and make choices in my day that reduce my exposure. But I’m looking at my fridge right now, and I can tell you most of my foods have come in contact with PFAS. We should regulate the entire class of chemicals and stop companies from manufacturing them to begin with, rather than try to regulate how much is in our water”.33 For additional information, visit: A Consumer’s Guide to PFAS: Side-Stepping ‘Forever Chemicals’ In Your Daily Life:

TELL CONGRESS TO PROTECT FARMERS AND THE PUBLIC FROM PFAS

“The use of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in industrial and commercial applications has led to widespread contamination of water and biosolids used for fertilizer…posing a significant threat to the biosphere, public health, gardens, parks, and agricultural systems. Farmers and rural communities, in particular, bear the brunt of this contamination, as it affects their drinking water, soil quality, and livestock health.”34 Tell Congress that the Farm Bill must include the Relief for Farmers Hit with PFAS Act and the Healthy H2O Act to protect farmers and rural communities from PFAS contamination. “Led by [Representative] Chellie Pingree (D-ME), U.S. Senators Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), and Susan Collins (R-ME), a bipartisan and bicameral bill—the Relief for Farmers Hit with PFAS Act—has been introduced to provide assistance and relief to those affected by PFAS. A second bill, the Healthy H2O Act, introduced by Representatives Pingree and David Rouzer (R-NC) and Senators Baldwin and Collins, provides grants for water testing and treatment technology directly to individuals and non-profits in rural communities.”34

Read more below about how to protect farmers’ health against PFAS contamination through passage of The Relief for Farmers Hit With PFAS Act and support the transition to producing alternative crops, including different types of grains, fruit, and root vegetables.

Op-ed: PFAS contamination endangers farmers’ health — a new federal program would empower them to address the crisis

https://www.ehn.org/maine-farm-pfas-2668601304.html

Federal leaders must step in and help farmers across the country navigate this pollution crisis.

“When dozens of Maine farmers discovered high levels of PFAS in their soil and water, our state’s agricultural community found itself on the verge of crisis.

These “forever chemicals” pose a grave risk to the food supply and to the farmers and their families working on contaminated land.

Farmers, advocates and leaders from across the state came together to develop a statewide response to PFAS contamination. Today, Maine is the first state to launch an emergency relief fund for impacted farmers and ban the use of sludge-based fertilizers that contain these dangerous chemicals. Maine’s response has reversed a hopeless situation for so many: of the 59 farms where PFAS was initially discovered, nearly all were able to weather a safe transition with this safety net in place. Now Congress is considering a federal program modeled after Maine’s emergency relief fund. The Relief for Farmers Hit With PFAS Act would authorize grants for states to provide financial assistance to affected farmers, expand monitoring and testing, remediate PFAS, or even help farmers relocate.

While Maine was the first to confront this problem head-on, the consequences of PFAS contamination extend far beyond this state. For decades, many states have encouraged farmers to spread sewage sludge on fields as fertilizer. Recently, scientists discovered that it contained dangerous chemicals that linger in the environment indefinitely – yet some states haven’t caught up and still push to spread the sludge. Testing for these chemicals is the only way to know if a farm is contaminated, but in the absence of federal guidance or regulations, few states are regularly doing so.

Without adequate monitoring, farmers not only risk financial ruin, but irreversible damage to their health. When PFAS seeps into a farm’s land and water, exposure poses serious health risks for anyone drinking contaminated water or consuming contaminated products, including kidney cancer, liver disease, thyroid disorders and autoimmune disorders. It’s still too early to predict the exact long-term outcomes, but we know it’s only a matter of time until research catches up to reality. One farmer with recently reported blood levels of PFAS at 3,500 parts per billion –175 times the level that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine says poses a serious risk – after years of drinking contaminated water on his farm. The previous owner of the farmland died of a cancer that we now believe may have been PFAS-linked.

Without adequate monitoring, farmers not only risk financial ruin, but irreversible damage to their health.

If we don’t plan for the future, more lives are at stake. If more states don’t begin to test their farmland, this crisis could continue affecting far more communities than we currently know. The good news is, once a farm is tested, there are options for farmers to move forward safely. Overhauling farms to produce different types of grains, fruit or root vegetables can significantly lower the risk of concentrating the chemicals. These transitions are safe, but expensive, and small businesses can’t afford this burden alone. That’s why a safety net is needed – more specifically, a safety net that gives farmers the healthcare and financial support they need.”35

CONCLUSION

Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are present in a wide range of consumer products including food, water, and food packaging. They bioaccumulate in our bodies over time and may be associated with serious health problems. By taking the above action steps, you can reduce your exposure to PFAS. However, there is a need for ongoing monitoring, improved testing, and enhanced government regulation to address the widespread occurrence of PFAS contamination in the environment.

REFERENCES

1. The Foodprint of PFAS. A Foodprint Report. Foodprint, a project of GRACE Communications Foundation. September 2023. (Updated November 2023). Web site. https://foodprint.org/reports/the-foodprint-of-pfas/#main-content Accessed April 10, 2024.

2. Gore AC, LaMerrill MA, Patisaul H, Sargis RM. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health. Pesticides, Plastics, Forever Chemicals and Beyond. Endocrine Society and International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN). Washington DC: Endocrine Society. February 26, 2024; p. vi. Published 2024. https://www.endocrine.org/news-and-advocacy/news-room/2024/latest-science-shows-endocrine-disrupting-chemicals-in-pose-health-threats-globally Accessed April 10, 2024.

3. Boudreau C, McFall-Johnsen M. Your drinking water could contain fewer hazardous ‘forever chemicals’ under new federal rules. Business Insider. Web site. April 10, 2024. https://www.businessinsider.com/epa-hazardous-forever-chemicals-drinking-water-limits-2024-4 Accessed April 10, 2024.

4. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). PFAS and Your Health. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention (CDC). Last updated on January 18, 2024. Web site. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects/exposure.html Accessed February 15, 2024.

5. Persellin K, Andrews D. ‘Forever chemicals’: Top 3 ways to lower your exposure. Environmental Working Group. February 15, 2024. Web site. https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/2024/02/forever-chemicals-top-3-ways-lower-your-exposure Accessed February 15, 2024.

6. Guidance on PFAS Exposure, Testing, and Clinical Follow-Up. Consensus Study Report. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington DC:2022.

7. Belcher S. PFAS Chemicals: EDCs Contaminating Our Water and Food Supply. Washington DC: Endocrine Society. Undated. Web site. https://www.endocrine.org/topics/edc/what-edcs-are/common-edcs/pfas Accessed February 15, 2024.

8. Cathey, A.L., Nguyen, V.K., Colacino, J.A. et al. Exploratory profiles of phenols, parabens, and per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances among NHANES study participants in association with previous cancer diagnoses. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2023;33: 687–698.

9. Zachariah JP, Jone PN, Agbaje AO, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Environmental Exposures and Pediatric Cardiology: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. 2024 Apr 15. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001234

10. Weiss MC, Wang L, Sargis RM. Hormonal injustice: Environmental toxicants as drivers of endocrine health disparities. Endocrin. Metab. Clin. 2023; 52(4): 719-736.

11. Abrams Z. Press Release. Longitudinal study links PFAS contamination with teas, processed meats and food packaging. Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California. February 5, 2024. Web site. https://keck.usc.edu/news/longitudinal-study-links-pfas-contamination-with-teas-processed-meats-and-food-packaging/ Accessed February 14, 2024.

12. Udasin S. Consumption of teas, takeout, hotdogs could come with a side of ‘forever chemicals. The Hill. February 6, 2024. Web site. https://thehill.com/policy/equilibrium-sustainability/4451162-forever-chemicals-pfas-tea-takeout-hot-dogs-consumption-linked-study/ Accessed February 14, 2024.

13. Hampson HE, Costello E, Walker DI. Associations of dietary intake and longitudinal measures of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in predominantly Hispanic young Adults: A multicohort study. Environ. Int. 2024;185:108454.

14. Tea bags, takeaways and hot dogs linked to high levels of forever chemicals, American study finds. Euronews Green. February 21, 2024. Web site. https://www.euronews.com/green/2024/02/20/tea-bags-takeaways-and-hot-dogs-linked-to-high-levels-of-forever-chemicals-american-study- Accessed February 22, 2024.

15. Jala A, Adye DR, Borkar RM. Occurrence and risk assessments of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in tea bags from India. Food Control. 2023;151:109812.

16. Phelps DW, Parkinson LV, Boucher JM, et al. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in food packaging: Migration, toxicity, and management strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024;58(13):5670–5684. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.3c03702.

17. Hemingway Jaynes, C. 68 PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ found by scientists in food packaging worldwide. EcoWatch. March 21, 2024. Web site. https://www.ecowatch.com/food-packaging-pfas-forever-chemicals.html Accessed March 21, 2024.

18. US FDA. FDA Announces PFAS Used in Grease-Proofing Agents for Food Packaging No Longer Being Sold in the U.S. February 28, 2024. Web site. https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-announces-pfas-used-grease-proofing-agents-food-packaging-no-longer-being-sold-us Accessed February 28, 2024.

19. Ackerman Grunfeld, D., Gilbert, D., Hou, J. et al. Underestimated burden of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in global surface waters and groundwaters. Nature Geoscience. 2024; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-024-01402-8

20. LaMotte S. Toxic ‘forever’ chemicals found in excessive levels in global groundwater, study says. CNN. April 9, 2024. Website. https://edition.cnn.com/2024/04/08/health/pfas-groundwater-global-contamination-scn-wellness/index.html Accessed April 9, 2024.

21. Amarelo M. EPA sets bold new limits on ‘forever chemicals’ in drinking water. Environmental Working Group. April 10, 2024. Web site. https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news-release/2024/04/epa-sets-bold-new-limits-forever-chemicals-drinking-water?utm_source=newsletter&utm_campaign=202404PFASNews&utm_medium=email&utm_content=PFAS&emci=3e0dd8ec-51f7-ee11-aaf0-7c1e52017038&emdi=460dd8ec-51f7-ee11-aaf0-7c1e52017038&ceid=1301962 Accessed April 10, 2024.

22. Perkins T. EPA has limited six ‘forever chemicals’ in drinking water – but there are 15,000. The Guardian. April 11, 2024. Web site. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/apr/11/pfas-limits-epa-drinking-water Accessed April 11, 2024.

23. Flamer K. How to Get PFAS Out of Your Drinking Water. Consumer Reports. April 10, 2024. Web site: https://www.consumerreports.org/water-contamination/how-to-get-pfas-out-of-your-drinking-water-a7303943293/ Accessed April 10, 2024.

24. 10 Things You Can Do About Toxic PFAS Chemicals. Clean Water Action. Undated. Web site. https://cleanwater.org/10-things-you-can-do-about-toxic-pfas-chemicals Accessed April 10, 2024.

25. University of Toronto. New study finds toxic PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ in Canadian fast-food packaging. Phys.Org. March 28, 2023. Web site. https://phys.org/news/2023-03-toxic-pfas-chemicals-canadian-fast-food.html Accessed April 10, 2024.

26. Schwartz-Narbonne H, Xia, C, Shalin A. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in Canadian fast food packaging. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2023;10:343-349.

27. BPI Certification. North America’s Leading Authority on Compostable Products & Packaging. Undated. Web site. https://bpiworld.org/ Accessed April 10, 2024.

28. Ginty MM. “Forever Chemicals” Called PFAS Show Up in Your Food, Clothes and Home. Natural Resources Defense Fund; Washington DC; April 10, 2024. Web site. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/forever-chemicals-called-pfas-show-your-food-clothes-and-home Accessed April 10, 2024.

29. Bear-McGuiness L. From PFAS to Microplastics, What Might Be Leaking Out of Your Teabag? Technology Networks, Applied Sciences. February 19, 2024. Web site. https://www.technologynetworks.com/applied-sciences/articles/from-pfas-to-microplastics-what-might-be-leaking-out-of-your-teabag-383985 Accessed February 20, 2024.

30. Boston’s Children’s Hospital. Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU) PFAS Food Factsheet. Boston, MA; February 2024. Web site. https://www.childrenshospital.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/PFAS-Fact-Sheet-2-2-2024.pdf Accessed February 15, 2024.

31. Barbo N, Stoiber T, Naidenko OV, Andrews DQ. Locally caught freshwater fish across the United States are likely a significant source of exposure to PFOS and other perfluorinated compounds. Environ Res. 2023;220:115165.

32. Crawford, K.A., Gallagher, L.G., Giffard, N.G. et al. Patterns of seafood consumption among New Hampshire residents suggest potential exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Expo Health. 2024; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12403-024-00640-w

33. McFall-Johnsen M. Hazardous ‘forever chemicals’ in water, food, and air won’t disappear with new EPA rules. But 6 simple tactics can reduce your exposure at home. Business Insider. September 17, 2022. Updated April 10, 2024. Web site. https://www.businessinsider.com/reduce-hazardous-forever-chemicals-exposure-pfas-at-home-2022-9 Accessed April 10, 2024.

34. Beyond Pesticides. Tell Congress To Protect Farmers and the Public from PFAS. Undated. Web site: https://secure.everyaction.com/w0Cs4OrV4kW1YJEBJIcy3g2?contactdata=8NN42zW7eVr4o%2fn%2fx3Fg1Lr1iX8qBp5W2q4JkyUsSV7+EEwyUPq8V5VvhSAmM4ZpSmoHSOYUcxy%2fxhNpheec3MstRv401VK8kjGlrGYLIBNN9TeQlQN7F8TvJPP0pzFvsJGTalhC0VsM36b1iKIdrd1Uu3FL1%2fypvk8zVLtBOyY9FqZu%2fdKboppnPWMKNea33HBhcidaRI6ryZAvObZFww%3d%3d&emci=fd171530-07cd-ee11-85f9-002248223794&emdi=9f404b35-a5cd-ee11-85f9-002248223794&ceid=10613815 Accessed May 11, 2024.

35. Alexander S. Op-ed: PFAS contamination endangers farmers’ health — a new federal program would empower them to address the crisis. Environmental Health News. June 26, 2024. Available at: https://www.ehn.org/maine-farm-pfas-2668601304.html